by Roxanne Tellier

(reprinted from DBAWIS, 2017/3/26)

It’s been nearly four months, and still, several times a day, it feels like a rat is trying to gnaw it’s way out of my belly. I’m still craving the instant hit of nicotine that was my constant companion for nearly 50 years.

I remember precisely when I first inhaled a Benson and Hedges menthol cigarette … I was 13 years old.

A friend had come in from Edmonton to enjoy the wonders of Montreal and Expo 67, and she brought me the habit. I’ve never forgotten that day. We giggled even as we gagged, and blew the smoke out of my bedroom window. I felt very grown up, as she showed me how to ‘French inhale.’

She also turned me on to shoplifting, but I was such a terrible thief that my first attempt in the downtown Woolworths found me nabbed and ‘barred for life’ from the store.

But back to cigarettes. My grandparents smoked into their nineties, and both of my parents smoked, as did most peoples’ parents back in the sixties. People smoked, and they smoked EVERYWHERE. At the local Steinbergs, a large grocery chain store, there were ashtrays affixed to the shopping carts, so that you need never go without your nic fix as you weighed your bananas.

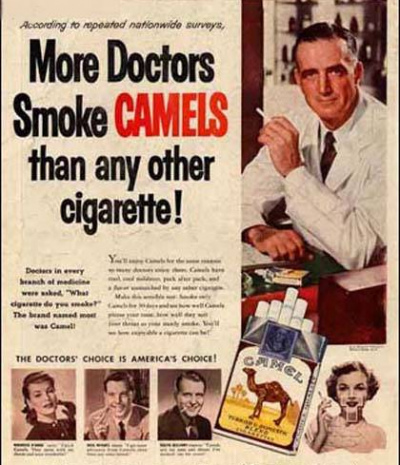

We smoked in offices, in hospitals, in church basements, in stores, on elevators, in restaurants, on the street, on airplanes, in our cars, and in our homes. MPs smoked in Parliament. Talking heads smoked during television interviewers. Doctors recommended brands in print and TV ads. Even cartoon characters smoked.

We smoked indoors and outdoors, and few, if any, ever waved a hand to shift the smoke from their faces, or the faces of their children.

At that time, 50% of Canadians over the age of 15 smoked. I’m guessing it was closer to 80% in Quebec, where no macho, hockey playing, swaggering boy would be seen without a fag hanging from his lip, and a deck tucked up inside his white t-shirt’s sleeve.

Cigarettes were quite inexpensive, less than fifty cents a pack, and were even cheaper in the States. The top tobacco brands competed fiercely for market share, in both Canada and the U.S., but the magazines that came from America almost always included coupons for free packets of ciggies.

But there had been rumours coming from the United Kingdom (where 80% of males smoked) as early as 1950, that a Dr Richard Doll had discovered a link between smoking and cancer, while pursuing a possible link between the tar in road construction and patients with lung, stomach, colon, or rectal cancer. Over a period of several years, he interviewed patients, and over 40,000 British physicians, and came to the inevitable conclusion that smoking was a main factor in lung disorders, cancer, and cardiovascular disease.

Since no one wanted to believe that our delicious smoking habit could possibly be bad for us, most people thought it was just some nonsense brought up by do-gooders who had a hate on for smokers and drinkers. After all, 9 out of 10 doctors said Camel cigarettes were ‘toastier,’ while dentists recommended Viceroys! Clearly your health and safety concerns were just a question of finding the right brand.

But the evidence was mounting. In 1963, Canada’s federal health minister, Judy LaMarsh, warned that smoking contributed to lung cancer, prompting the Canadian Medical Association to urge doctors to stop smoking, at least while attending their patients.

And despite the 1964 report from the U.S. Surgeon General that linked cigarette smoking to lung cancer in men, and possibly in women, despite that same report citing smoking as the most important cause of chronic bronchitis, and despite the fact that I was studying voice and music, and considering a career as a vocalist … I took up smoking in 1967 and didn’t look back for decades.

In 1972, the first ‘warning’ messages began to appear on the side of cigarette packages, and by 1989, it was made mandatory for packets to have a health warning . By 2001, Canada mandated picture warnings that covered 50 per cent of the boxes.

Like most conscientious, quasi-hippies of the sixties, I quit smoking and drinking while pregnant with my daughter, and stayed off cigarettes for a few years after her birth. But nicotine is highly addictive, so by 1976, I was back on the demon weed, despite now pursuing full time singing gigs. I was young, healthy, and I couldn’t feel any side effects from my habit, so why not?

For a few years I’d continue on an on-again/off-again pattern, quitting sometimes for years at a time. But despite trying every trick in the book, from acupuncture to hypnotism to counselling and medication, nothing worked permanently. I was always just an excuse away from sliding back into the addiction.

And then, about four years ago, I heard about a paid research study on nicotine addiction being done by CAMH, (the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health Care,) and decided to give it a go. They’d pay me to be in a double blind study that focused on the use of Zyban, a nicotine replacement medication. AND they’d give me the medication for free. Only thing was, I wouldn’t know if I was on the actual drug or a placebo. Still, I was game to give it a whirl.

Beyond the medication, the study focused on mindfulness, and an understanding of what part our addiction played in our day to day lives. The study required that I make a note of every cigarette I smoked during the day, and any emotion I was feeling when I felt the urge to smoke. Since I had been using an old fashioned cigarette making machine with tobacco and tubes for my daily fix, I hadn’t any idea that my cigarette intake had risen to 40 cigarettes a day.

I also discovered that I had certain attitudes about smoking. Years of social conditioning had convinced me that I could neither relax nor concentrate without a smoke, and that I certainly couldn’t write without a cigarette smouldering away in the full ashtray beside me.

When I’d talk to other smokers, the males would commonly exhibit bravado about continuing to smoke, despite health concerns, while most of the women would agree that sneaking a cigarette break really meant allowing themselves to stop the world and it’s unending demands for a minute. Even though we intuitively knew that we were doing physical damage to our bodies by smoking, we still had a “this I do for me” attitude about the habit.

When the study concluded, I was nervous about keeping off the ciggies on my own, so I was referred to the CAMH Nicotine Independence Clinic, where I would have access to outpatient treatments, assessment, medical consultation, group counselling and medications to quit/reduce smoking.

I’m so glad that I lucked into that clinic. From my first visit, I was welcomed by their friendly staff, and treated by top notch doctors and nurses that encouraged me to fight towards nicotine independence. Month after month I’d have to face those professionals and explain why I, an intelligent, motivated, woman, could not seem to get the nicotine monkey off my back.

The first surprise was that I had spent three months on the placebo, rather than the medication. And when I was prescribed the actual Zyban, I discovered that I couldn’t tolerate the drug; I wasn’t smoking, but only because I couldn’t stop vomiting.

However, with the clinic’s support, and a constant supply of free nicotine replacement treatments, (patches, lozenges, gums, inhalers) I struggled through the next four years, promising myself and my mentors that I would indeed quit .. soon. Just not today.

During a particularly harsh Harper budget year, the rules for the clinic were changed; patients could now only receive the nicotine replacements for six months at a time, although they could continue receiving medical consultations and counselling. After a further six months, patients could again receive replacements. Those six months on/six months off made it very hard for many to stay nicotine free.

When I returned to the clinic last fall to begin yet another six months of treatment, I desperately wanted to get off the addiction treadmill. I was sick of being sick, of seeing the effects of years of nicotine use etched on my face, and in it’s detrimental effects on my health. It had almost become a joke that I had been attending the Clinic for longer than some of their staff.

I waved a breezy ‘hello’ to Natalie, the receptionist. But it was the sight of a woman patiently waiting to see the doctor that really gave me pause. The woman was chipper and in good spirits, despite being hooked up to oxygen tanks, and needing a walker to get around. She happily told me that she was certain she could finally quit smoking, although it was too late to do much more than halt the progress of the COPD (Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease) that she’d acquired through her years of smoking. The woman confided that she was a decade younger than me.

When it was my turn to talk to the doctor, I told him that I could deal with aging, but I couldn’t deal with being a sick old lady. I wanted to bang away at this nicotine monkey with everything I had, and that they could give me. The doc loaded me up with patches, gum, lozenges and inhalers, and wished me good luck.

For all my good intentions, however, and even while wearing nicotine patches that added up to 63 milligrams of nicotine replacement to my blood, I still found myself smoking to ease tensions and relax. I could tell myself that the stress of selling the house and moving gave me an ‘out.’ I DESERVED the occasional cigarette, dammit!

And the story might have ended there, in an endless loop of me going to the clinic, getting medical help, and still smoking, except for a bad thing that turned out to be a good thing.

November and December were tough months, what with the move, the weather, and all of the physical changes in my life, which culminated in a bunch of health issues, including a cold that turned into bronchitis and then into a nagging cough that just wouldn’t go away. I coughed 24/7, even in my sleep. I coughed so constantly and theatrically that I finally had to find a new doctor that might be able to help me stop coughing, and allow everyone to get a decent night’s sleep.

This doctor listened patiently to my story, and then produced a medication. “The good news, ” he said, “is that this medication will stop the cough. The bad news is that, if this medication works, you likely have COPD. We’ll have to do testing to find out if that is the case.”

In that moment, time stood still.

Although I’d have to wait a week for the tests to be done and assessed, I knew that I had finally passed the threshold I’d always dreaded; I had done terrible damage to my lungs, and now I’d have to pay the price.

I stopped smoking that day, nearly four months ago, and haven’t had a cigarette since. The tests came back, and although I’d done a lot of damage to my lungs with the smoking and the coughing, I did not have COPD. With care, and time, the damage would repair itself. All I had to do was not smoke.

So I didn’t. And I won’t. Even when the craving is so intense that I feel like screaming, my mind flashes back to that moment in the doctor’s office, and I don’t light up. I dodged a bullet – no way will I put myself back in it’s path again.

I’m still wearing the nicotine patches, although with time, I’ll wean myself off them. And I have nicotine replacement inhalers in every pocket, purse and room of the house. I have the support of my family, friends, and doctors, all of whom remain cautiously optimistic that I’ll keep on the straight and narrow.

I’m not saying it’s easy, nor am I throwing myself a ticker tape parade, but I’m very grateful for the help and support I’ve received, and quietly confidant that I’m too sensible to let my addiction wiggle it’s way back into my life.

I smell better. My clothes and my house smell better. I no longer have to worry if my smoking will harm other people, nor do I have to fear long periods of time in places where you can’t smoke. I don’t have to leave an event and traipse out into the cold or rain to have a ciggie. I don’t look up at a darkening sky and wonder if I have enough cigarettes to last through a snow storm. I don’t have to calculate the cost of cigarettes into my budget.

I no longer have to justify a habit that took the lives of my father and mother, amongst other millions of smokers.

I am a non-smoker.

(originally published 2017/3/26, on Bob Segarini’s Don’t Believe A Word I Say website)

It is important that you reward yourself for doing this. I got a cleaning person when I quit. Cheaper than the smokes and I never have to clean a toilet again.

After 17 years I still occasionally get an intense but brief craving. I can shake them off easily now but it does take time.

Good luck. Life will be better when you stick to it.

Thanks! I wrote this back in 2017, so I’m a long way from the first terrible panic of cravings … now it’s just maybe once in a blue moon. Funny though, that monkey never really lets go; it’ll be on your back forever. Best thing I ever did was quit smoking … and staying quit. 😉